Date: July 15, 2013

July 15, 2013

|

|

| Dr. Chibli Mallat received his PhD from the law department of the School for Oriental Studies in London and has been a leading civil society activist in Lebanon and the Middle East region for roughly 30 years. He currently holds the Presidential Chair for Middle Eastern Law and Politics at the University of Utah and the EU Jean Monnet Chair of European Law at Saint Joseph University in Lebanon. |

Mr. Mallat is the son of lawyer Wajdi Mallat, who served as the first president of the Lebanese constitutional council and was named for his grandfather, who was known as "the Poet of the Cedars." Mr. Mallat began to advocate human rights during Lebanon's war-torn 1980s, and he received his PhD from the law department of the renowned School of Oriental and African Studies in London. Since then, he has held positions at a number of international universities, including the University of Virginia, Princeton, Harvard and the University of Lyon. Locally, he has been a faculty member at institutions such as Université Saint Joseph and the Islamic University of Lebanon. Rather than maintaining a focus on developments occurring within his own sectarian community, Mr. Mallat's earliest academic works identify him as having an interest in far-reaching Lebanese issues. For instance, he earned a reputation within the country’s Shia milieu for the attention he paid to the changes which affected that community, particularly when such developments were considered exclusively Shia in nature. His 1993 book, "The Renewal of Islamic Law: Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr, Najaf, and the Shi’i International," which received the prestigious Albert Hourani award for excellence in Middle Eastern Studies publications, is a brilliant illustration of Mr. Mallat's early emphasis on the Shia community. It also distinguished him as someone capable of exerting substantial influence on the development of political Islam in the pan-Shia community. Aside from his academic interest in Shia issues, Mr. Mallat has accumulated a sizeable registry of legal cases involving the Shia community at large. Of note, Mr. Mallat has brought to trial a number of highprofile cases since the early 2000s, including one against the late Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, and another against the late Libyan dictator Moammar Gaddafi (which focused on the 1978 disappearance of Lebanese Shia cleric Imam Musa as-Sadr).

In addition to his vast legal work, Mr. Mallat joined the race to unseat former President Emile Lahhoud due to Mr. Lahhoud's "novel" three-year extension of his mandate. Mr. Mallat's campaign, which focused on redressing the clearly illegal nature of that extension, was cut short only by the July 2006 war. Yet, Mr. Mallat’s extensive list of qualifications does not identify him as being preoccupied with attaining political power and support. Rather, they showcase an individual who has always pushed Lebanon to respect and uphold its democratic foundations. Importantly, as Lebanon becomes increasingly interconnected, Mr. Mallat is the perfect example of an intellectual and legal professional who eschews limited insight. Instead, he has developed a keen sense of the events occurring around him—events not restricted to his own community.

The following is the text of a brief interview about Mr. Mallat's achievements, the work with which he is currently involved and his vision for Lebanon.

Your career is certainly international, considering you received your PhD from London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies and have held positions as a lecturer and professor in a number of US and European universities. How did your early experiences in Lebanon impact your work as a legal expert in these countries? Conversely, did your time abroad influence your attitude about the Lebanese political and judicial systems?

Although Lebanon is a small country, it is a wonderful laboratory for cultures and languages. To my knowledge, it remains the only place on the planet where Arabic, French and English interact at a cultural level, and where the critical mass of linguistic actors produces more than just convenience for business or an expat intellectual community. But the Lebanese are more than mere polyglots. Many function culturally in those three languages, so despite its insecurity and lack of political integration, Beirut’s cosmopolitan nature makes it an attractive destination for visitors from the East and West. I grew up in that cosmopolitan Beirut before it experienced the civil war inferno, and I cherish my internationalism; it is not something that is superficial in the country. Naturally, that characteristic helped me adapt to places where people like me were forced by the conflict to take refuge, whether temporarily or for the long term. Reviewing the five decades of my life, I recognize a pattern: I never left the country permanently, but I needed to be away, sometimes for a long while, to establish a more secure basis for my family and myself. The outcome was a matter of luck, mostly, and hard work, of course, but Lebanon gave me a cultural basis, which made things so much easier. In France, where I completed my last year of high school, I felt at home in the culture, as did many Lebanese. Much later, in the UK and the US, my ability to discuss Shakespeare with colleagues enabled me to overcome barriers that would otherwise have taken me a very long time to surmount. So, I am grateful to Lebanon—and my parents, who encouraged my cosmopolitanism—for providing such an extraordinary platform for cultural adaptability. There was certainly a heavy price associated with that instability, not to mention the world's loss of my generation and Lebanon's inability to profit from it.

The reverse influence is no less special: I often advise students to take every opportunity to look at the world from different geographical perspectives. In France, where I was suddenly thrown into a world in which Foucault, Althusser and Deleuze are read and discussed, I realized the antiquated nature of our Beirut-based study of French culture, with its obsession for conservative classics. Similarly, when I arrived in DC for the first time in the summer of 1982 to start my LLM, it took me two days to comprehend how insignificant Lebanon was, despite its being in the midst of the Israeli invasion.

Lebanon's sclerotic political system, with its dysfunctional sectarianism, appears quite odd in a country where the "ethnolysis" (a word coined by French writer Robert Fossaert) produced sufficient commonalty between "ethnies" (sects in Lebanon) to foster a working government. But sectarianism is stubborn, and papering it over with secularism is difficult. For me as Lebanese, it was a genuine cultural shock when I discovered the U.S. Supreme Court—its ongoing debates, and the scholarship and respect it commands throughout the country. Courts in the Middle East pale in comparison. My first scholarly law article focused on the U.S. Supreme Court, and my dear former professor and family friend, Ibrahim Najjar, encouraged me by publishing it in 1986, in Arabic and French, in the journal of the USJ.

To what extent do you believe the Syrian situation has and will continue to foment sectarianism in Lebanon? Do you believe Syria is pushing Lebanon towards war?

The case against Gaddafi was begun in Lebanon in 2001 by the families of the three disappeared. We got an indictment for Gaddafi by the Lebanese Prosecutor-General in 2004, just as Gaddafi was becoming the darling of the world, when the Lockerbie trial yielded blood money for the victims instead of an indictment and prison for Gaddafi. Thanks to the dedication of the Sadr family and the support of the Yaqoub and Badreddine families, our case held a uniquely tight focus of resistance against Gaddafi despite the global red carpet treatment he was receiving at the time. As with the INDICT work, the Sadr case expressed the power of the victims of dictators, and the idea eventually found its way to the ongoing trials of Mubarak and ben Ali. Indeed, Saddam and Gaddafi were terrorized and angered by the cases built against them. These legal initiatives were truly novel, and my academic and legal peers were generally intrigued and supportive. This was uncharted terrain from an international legal perspective, and despite the setbacks, it was formidable. Working on these cases was exhausting and exhilarating, and I learned a great deal. The teamwork that accompanied those endeavors advanced international law by leaps and bounds (usually a glacial process), and the dictators became frightened of activities that their brutal forces had difficulty subduing. Ultimately, these trials shaped my awareness of the intimate connection between nonviolent revolution and judicial accountability.

In 2003, you brought a case to court in Belgium against Ariel Sharon on behalf of the Sabra and Shatila victims. Notably, that case was eventually overturned due to jurisdictional considerations. What did you learn from that experience in terms of utilizing the international community and court systems to try regional issues? Do you believe that international mechanisms such as the STL or the ICC are appropriate for dealing with human rights issues in the MENA region? Do you believe other options exist within the country’s own court systems?

Much of your work seems to address the Shia community in the Middle East. Is your interest in Shia issues merely coincidental?

RN was established in 2009 in Beirut and focuses on three primary areas: nonviolence as the exclusive tool to achieve historic change; constitutionalism as the means to institutionalize change within a proper democratic framework and justice for the victims of dictators. Justice against dictatorship as a “crime against humanity” must be served before a court, preferably a domestic one, in cases that involve dictators and their most brutal aides. With respect to Gaddafi’s son and his security man, the ICC has indicted them—to the great relief of the victims—but a complicated game is still being played out between the Libyan jurisdiction and the international court. In general, courts are decimated after three or four decades of dictatorship, so the successor government has little ground to build on. Since those new governments are fragile, my preference in these big cases is to obtain professional support from people experienced in such trials. Of course, courts are also needed for everyday life, and it takes at least a decade to create a new generation of judges with the courage to counter the heavy hand of the executive branch.

Although Lebanon is a small country, it is a wonderful laboratory for cultures and languages. To my knowledge, it remains the only place on the planet where Arabic, French and English interact at a cultural level, and where the critical mass of linguistic actors produces more than just convenience for business or an expat intellectual community. But the Lebanese are more than mere polyglots. Many function culturally in those three languages, so despite its insecurity and lack of political integration, Beirut’s cosmopolitan nature makes it an attractive destination for visitors from the East and West. I grew up in that cosmopolitan Beirut before it experienced the civil war inferno, and I cherish my internationalism; it is not something that is superficial in the country. Naturally, that characteristic helped me adapt to places where people like me were forced by the conflict to take refuge, whether temporarily or for the long term. Reviewing the five decades of my life, I recognize a pattern: I never left the country permanently, but I needed to be away, sometimes for a long while, to establish a more secure basis for my family and myself. The outcome was a matter of luck, mostly, and hard work, of course, but Lebanon gave me a cultural basis, which made things so much easier. In France, where I completed my last year of high school, I felt at home in the culture, as did many Lebanese. Much later, in the UK and the US, my ability to discuss Shakespeare with colleagues enabled me to overcome barriers that would otherwise have taken me a very long time to surmount. So, I am grateful to Lebanon—and my parents, who encouraged my cosmopolitanism—for providing such an extraordinary platform for cultural adaptability. There was certainly a heavy price associated with that instability, not to mention the world's loss of my generation and Lebanon's inability to profit from it.

|

| The masthead from the "Chibli Mallat for President" website launched in 2005. As Mr. Mallat remarked in this interview, his campaign focused on redressing the clearly illegal nature of the three-year extension to former President Emile Lahhoud’s mandate. |

Lebanon's sclerotic political system, with its dysfunctional sectarianism, appears quite odd in a country where the "ethnolysis" (a word coined by French writer Robert Fossaert) produced sufficient commonalty between "ethnies" (sects in Lebanon) to foster a working government. But sectarianism is stubborn, and papering it over with secularism is difficult. For me as Lebanese, it was a genuine cultural shock when I discovered the U.S. Supreme Court—its ongoing debates, and the scholarship and respect it commands throughout the country. Courts in the Middle East pale in comparison. My first scholarly law article focused on the U.S. Supreme Court, and my dear former professor and family friend, Ibrahim Najjar, encouraged me by publishing it in 1986, in Arabic and French, in the journal of the USJ.

In 2005, you challenged Emile Lahhoud for the presidency. Lahhoud was eventually appointed through a controversial constitutional extension of his mandate. Your campaign was cut short by the July War. Can you talk more about the goals and experiences of your campaign and whether we might expect to see you again in the political arena? What future do you see for Lebanese politics?

I ran to dislodge Emile Lahhoud, who brought catastrophe to the country by forcing an extension of his presidential mandate after, as has been documented, the Syrian president threatened Rafik Hariri to acquiesce—which he did. I had no particular interest in the presidency and had warned Lahhoud on television six months earlier, then again in the papers—in an an-Nahar op-ed I sent from Australia, no less—on the eve of the three-year extension. The disaster followed soon after when resistance to the aspiring dictator persisted, and Marwan Hamade and then Rafik Hariri were consumed in devastating bomb attacks—all Lahhoud’s fault. Despite the massive revolution, he refused to leave, so I entered the race. It was an unprecedented campaign in Lebanon's medieval politics, which focused on the country's need to evict a budding dictator because of his disastrous practices. Even though we did not win the election, we made Lahhoud a pariah at home and abroad. He hung on for varying reasons, including the July War, which traded domestic pressure for a useless and ugly devastation of the country. Still, something remarkable happened: the Arab world saw the importance of confronting dictators. The revolutions that began in 2011 were focused on telling the dictators to leave, which is something I tried to steer the Cedar Revolution towards, but without success.

I don’t know what my political future will be. Lebanon is small and hard to govern, so even if becoming its president was possible, sitting in Baabda without the power to achieve change is unattractive. The present focus of my energies, which is more Middle Eastern in nature and somewhat more abstract, brings better rewards. It would be useful to have a stronger platform than an NGO or an academic position, but holding public office certainly introduces many constraints.

I don’t know what my political future will be. Lebanon is small and hard to govern, so even if becoming its president was possible, sitting in Baabda without the power to achieve change is unattractive. The present focus of my energies, which is more Middle Eastern in nature and somewhat more abstract, brings better rewards. It would be useful to have a stronger platform than an NGO or an academic position, but holding public office certainly introduces many constraints.

|

|

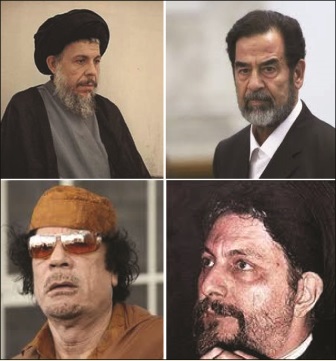

| Twice in his life, Mr. Mallat has been an advocate for the causes of two different clerics, Mohammad Baqer and Moussa, both of whom are members of the as-Sadr family. He also confronted two imposing Arab dictators, Saddam Hussein and Moammar Gaddafi (both of whom were Sunni). Clockwise from the top right: former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, Lebanese Imam Musa as-Sadr, former Libyan President Moammar Gaddafi and Iraqi Sayyed Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr. |

Regarding the future of Lebanese politics, it will be a miracle if we can escape a full-fledged Sunni-Shia war. But even if we are so lucky, we all know that after people kill each other for years and carry out ethnic cleansing in mixed cities, particularly Beirut, we still must live together again. Paradoxically, that certainty creates the only hope for the country because we are relying today on the collective memory we built to prevent Lebanon's full collapse.

To what extent do you believe the Syrian situation has and will continue to foment sectarianism in Lebanon? Do you believe Syria is pushing Lebanon towards war?

As was clear from day one of the revolution on March 16, 2011, Syria will determine the fate of the region. The classic move of an entrenched dictator is to turn the conflict sectarian and claim that his departure would open the gates of hell. Lebanon is but a footnote to the political earthquake that hit Damascus after Tunis and Cairo.... I have no doubt that Assad is pushing Lebanon towards war. He has even gotten Hezbollah to fight openly on his side within Syria. But the backlash, the anger with Shia throughout the Arab world—as we saw with the horrible killings in Cairo—is also real. The nuance is the degree of influence he can wield with the local protagonists, and that picture varies day by day.

You've also been engaged for a long time in human rights advocacy and democratic reform. One of your earliest endeavors was the establishment of INDICT, a campaign against the former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. You later won a case against former Libyan dictator Moammar Gaddafi on behalf of the Lebanese relatives of “disappeared” Imam Musa al-Sadr and his companions Abbas Badreddine and Muhammad Ya’qub back when few regional actors were willing to confront such regimes. Could you please describe those experiences? How did your peers view these cases, and what impact did they have on your other work?

Each of these stories is long and complicated. Moreover, each has been the subject of substantial legal research, long meetings, extensive travel and the tremendous amount of work required to bring such dictators to court. Let me try to describe briefly the two cases you mentioned.

INDICT was established in 1996, but my work to depose Saddam began with the International Committee for a Free Iraq. That group, established in London in June 1991, was comprised of some 50 leading Iraqis from the opposition, including colleagues like Jalal Talibani, the current president of Iraq, and Sayyed Muhammad Bahr al-‘Ulum, the first president of the Iraqi Governing Council. There were also remarkable people on the international and Arab sides, such as John McCain and the late Claiborne Pell (who led the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee at the time) and prominent Arab colleagues Saadeddine Ibrahim, Usama Ghazali Harb and Adonis, just to name a few. This unprecedented and impressive group worked openly for Saddam's exit, including the Kurdish "safe haven" (now called the nofly zone), the need for judicial accountability, Human rights monitors and so on. The ICFI was an important stepping-stone for the emergence of a unified opposition based on democracy in Iraq, but the 1994 civil war between the two main Kurdish factions frustrated the process. I took my leave from the opposition when it united to become the Iraqi National Congress (which today is a shadow of its former self) but reengaged in 1996 at a meeting between Hoshyar Zebari, the current foreign minister, and Barham Saleh, the current PM of the Kurdish region, with help from Richard Murphy at the Council on Foreign Relations. I started INDICT at that time, after securing the principled support of the Kuwaiti ambassador in London, with the objective of bringing Saddam to trial. We had remarkable support in Congress and in the House of Commons, and both Clinton and Blair are on record repeatedly for their support of INDICT. Had it actually progressed to the international tribunal it was advocating, things would have been very different for Iraq. Still, it laid some of the groundwork for Saddam's trial. The case against Gaddafi was begun in Lebanon in 2001 by the families of the three disappeared. We got an indictment for Gaddafi by the Lebanese Prosecutor-General in 2004, just as Gaddafi was becoming the darling of the world, when the Lockerbie trial yielded blood money for the victims instead of an indictment and prison for Gaddafi. Thanks to the dedication of the Sadr family and the support of the Yaqoub and Badreddine families, our case held a uniquely tight focus of resistance against Gaddafi despite the global red carpet treatment he was receiving at the time. As with the INDICT work, the Sadr case expressed the power of the victims of dictators, and the idea eventually found its way to the ongoing trials of Mubarak and ben Ali. Indeed, Saddam and Gaddafi were terrorized and angered by the cases built against them. These legal initiatives were truly novel, and my academic and legal peers were generally intrigued and supportive. This was uncharted terrain from an international legal perspective, and despite the setbacks, it was formidable. Working on these cases was exhausting and exhilarating, and I learned a great deal. The teamwork that accompanied those endeavors advanced international law by leaps and bounds (usually a glacial process), and the dictators became frightened of activities that their brutal forces had difficulty subduing. Ultimately, these trials shaped my awareness of the intimate connection between nonviolent revolution and judicial accountability.

In 2003, you brought a case to court in Belgium against Ariel Sharon on behalf of the Sabra and Shatila victims. Notably, that case was eventually overturned due to jurisdictional considerations. What did you learn from that experience in terms of utilizing the international community and court systems to try regional issues? Do you believe that international mechanisms such as the STL or the ICC are appropriate for dealing with human rights issues in the MENA region? Do you believe other options exist within the country’s own court systems?

The case was lodged in Belgium on June 18, 2001, and we won before the Belgian Supreme Court (the Court of Cassation) on February 12, 2003. That historic judgment still stands, so the Sabra and Shatila plaintiffs had their day in court and won. Unfortunately, the law was changed retroactively to remove Belgium's jurisdictional basis due to immense pressure by the U.S. government at the time.

Again, these are extraordinarily challenging cases that are intimately connected with politics. Thus, there is never a clear-cut result when unprincipled politics compete with the course of justice. As a matter of law, there is complementarity between domestic and international courts, such that if a fair trial can be conducted domestically, that is the preferred route. When the local judiciary fails, the international route should be considered. In working towards the STL, I suggested that we could have the best of both worlds in a mixed tribunal on which the STL is modeled. But there is never an ideal solution, as we saw by the failure of the international investigators to take note of what they were being asked by an entire people and the constraints placed on the Lebanese judges sitting on the STL.

Again, these are extraordinarily challenging cases that are intimately connected with politics. Thus, there is never a clear-cut result when unprincipled politics compete with the course of justice. As a matter of law, there is complementarity between domestic and international courts, such that if a fair trial can be conducted domestically, that is the preferred route. When the local judiciary fails, the international route should be considered. In working towards the STL, I suggested that we could have the best of both worlds in a mixed tribunal on which the STL is modeled. But there is never an ideal solution, as we saw by the failure of the international investigators to take note of what they were being asked by an entire people and the constraints placed on the Lebanese judges sitting on the STL.

Much of your work seems to address the Shia community in the Middle East. Is your interest in Shia issues merely coincidental?

Like all populations, the Shia community represents a wonderful journey of discovery from outside and from within, and I do not think I stumbled onto that interest by chance.

For instance, my father was friends with Imam Musa Sadr, and he engaged in some early human rights work with the late Me Mohsen Slim. But in general, my discovery of the world-class intellectual capacity of the late Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr and commitment to an Iraq free of Saddam Hussein propelled me to engage with Shia concerns. Sadly, my assessment in the early 1980s that Iraq represented the Middle East's key turning point—which shaped my interest in Islamic law—and my work on Baqer as-Sadr, proved true. It has since reinforced the work I have done on many different levels. I fear this Sunni-Shia animosity will eventually spiral down to Armageddon.Your current work focuses on the Arab Spring revolutions and the "Right to Nonviolence" theory. Could you please describe the work of that NGO and how you are supporting post-revolution judicial reform throughout the region?

|

|

| The cover of the Arabic translation of Mr. Mallat’s book, "The Renewal of Islamic Law: Muhammad Baqer as-Sadr, Najaf, and the Shi’I International." The book received the Albert Hourani award, the highest recognition given to works in the field of Middle Eastern Studies. |

RN has a formidable agenda, an extraordinary team and a Board that includes prominent academics and practitioners worldwide— from Princeton, Harvard and Yale, to colleagues from Bahrain, Egypt, Syria and China. We have limited means and do what we can, but I do not believe we can institute a full-blown, post-revolution judicial reform, since doing so would require that the ministers of justice play the leading role. Yet we can offer theoretical guidelines and comment critically on the work being done by those courts. We also focus on the new generation of "constitutional advocates", and this has already helped to create an impressive network of new and dedicated talent. Today, we are completing a project on constitutionalism with support from the National Endowment for Democracy, and I recently chaired a conference in Tripoli, Libya to join some of the best minds in Islamic law with others focused on international human rights. I am just back from Yemen, where I tried to help my old friend and colleague Dr. Jamal Benomar with the constitutional process in that country. What he has achieved so far as Special UN Envoy in the National Dialogue of Yemen is nothing short of miraculous, with people meeting every day to air their grievances and look for common solutions within the framework that should materialize in an upcoming national constitution. I know Jamal from my early days teaching at SOAS during the early 1990s. He was with Amnesty International and was a highly respected former prisoner of opinion in Morocco, where he spent several years in jail.

But my most enduring work is now focused on a book titled "Philosophy of Nonviolence" (hopefully to be published in early 2014), the ambitious thesis of which is to map the basis of nonviolence, constitutionalism and judicial accountability in the Middle East revolutions. The book benefits a great deal from RN’s collective efforts during the last four years.

But my most enduring work is now focused on a book titled "Philosophy of Nonviolence" (hopefully to be published in early 2014), the ambitious thesis of which is to map the basis of nonviolence, constitutionalism and judicial accountability in the Middle East revolutions. The book benefits a great deal from RN’s collective efforts during the last four years.

----------------------------------------

Interview by Kelly Stedem

-----------------------------------------

Interview by Kelly Stedem

-----------------------------------------

Print

Print Share

Share