February 9, 2015

Near the end of a two and a half hour interview with Hezbollah’s secretary general broadcast January 15 by al-Mayadeen television, host Ghassan ben Jeddo asked, “Speaking frankly, do you believe the social and sectarian milieu still supports you [Hezbollah] and represents a viable core?” Sayyed Nasrallah responds affirmatively. As proof, he refers to some public opinion surveys conducted by “research centers” managed by “Shia Americans,” and he made sure to note that those involved were “Shia connected to the American Embassy.”

Of course, his mention of “research centers” was a direct reference to Hayya Bina, and the survey he acknowledged was the February 2014 Hayya Bina poll, the results of which were published the following August in Arabic and English.

Apparent in Nasrallah’s comments is the common, paranoid obsession that sees the hand of the “American Embassy” behind all such research efforts. Similarly, his indiscriminate reference to the Hayya Bina poll is yet another reiteration of the joint Nasrallah/Hezbollah argument that seeks to assert the organization’s righteousness by emphasizing the credibility of literature produced by their political opponents (or enemies)...as long as those “sources” support their allegations. Beyond these anecdotal facts, Nasrallah’s mere reference to the Hayya Bina poll instantly enhanced its reliability and publicity—even though the responses collected via that poll are not always favorable to his organization. Thus, we owe Sayyed Nasrallah a debt of gratitude for having acknowledged the very best way to measure Hezbollah’s popularity within the Shia community.

Hezbollah often refers to its constituency as al-biaa al-hadina or Joumhour al-Moqawama (“the lapping environment” and “the public of the Resistance,” respectively). While these terms are often used interchangeably, their connotation is anything but similar.

In a nutshell, Joumhour al-Moqawama is far less restrictive than al-biaa al-hadina, as the former encompasses everyone who supports “the Resistance” regardless of sectarian affiliation or nationality. Conversely, the inclusiveness of Joumhour al-Moqawama, which has no preconditions for membership, differs substantially from al-biaa al-hadina, which refers more exclusively to the larger Shia community with its semantic complement of intimacy and worldliness.

Much to his credit, al-Mayadeen host Ghassan ben Jeddo chose not to whitewash his pivotal question. Instead, he remained on point by asking about the “the lapping environment,” i.e., the Shia community. But while the true nature of the question seems clear, it requires additional illumination.

In Lebanon, discussions about political representation of the Lebanese Shia community typically utilize “local” parlance to identify the “Shia duo,” comprised of Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, as the pillars of that representation. And while both organizations have their respective MPs, ministers and other shares of the Lebanese pie, when the discussion centers on “the lapping environment,” we seem to overlook that inherent division and focus instead on something beyond. In reality, however, Hezbollah’s popularity is not a partisan issue! After all, whether we like it or not, that vague reference to Hezbollah also encompasses its organizational affiliates and clientele-oriented architecture, both of which enjoy bits and pieces of Hezbollah’s share of the Lebanese pie. Thus, when we describe Hezbollah’s “lapping environment,” the larger Lebanese Shia community is automatically inferred. Clearly, the same cannot be said for the Amal Movement. Moreover, the question bin Jeddo asked of Nasrallah simply could not be answered by Nabih Berri (the Amal head). Despite the fact that Berri sees himself as heir to Sayyed Moussa Sadr (to whom the Lebanese Shia community owes its ascendancy on Lebanon’s political horizon), Sadr’s populist legacy and eventual “Movement of the Deprived” (the forerunner of the Amal Movement) seem to have shifted toward Hezbollah. A nostalgic, former senior Amal personality describes that transformation in militaristic terms: “Amal’s constituency is ‘occupied’ to a large extent by Hezbollah.” Unfortunately, although this metaphor is tempting because it suggests that simply undoing that “occupation” would force a return to the status quo ante, it fails to account for today’s sectarian related identity polarization (in Lebanon and throughout the region). Under this still emerging model, within-group partisan competition is no longer based on programmatic rivalry but on whom can best represent, protect and advocate the interests of a given sect in the face of other sects. Clearly, the matter of perception changes the situation little if at all.

In view of the foregoing, the logical conclusion is that no one in Lebanon—at least in the near term—can emerge as a viable competitor to Hezbollah. Consequently, questioning Hezbollah’s popularity among Lebanese Shia revolves less around the organization gaining or losing popularity vis-à-vis other competitors than it does to political cohesion within the community—or at least the image of unity and self-confidence to which the mainstream portion of that community subscribes. Further, an appreciation of this conceptual framework is necessary before one can genuinely understand the developments that began to unfold on January 18, 2015. That Sunday, Israel Defense Forces (IDF) helicopters attacked a joint Hezbollah-Iranian Revolutionary Guard convoy in Quneitira killing those in the two vehicles targeted, including an Iranian general and the son of Imam Mughniyyeh. Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah finally appeared January 30—on a mega screen—to comment on Hezbollah’s retaliatory attack conducted two days before in the contested Shebaa farms region.

Much has already been, and will continue to be said about Nasrallah’s speech, particularly his announcement that “the Quneitira attack also destroyed the rules of engagement that had previously governed military confrontations between Hezbollah and Israel in south Lebanon.” Assuming an-Nahar is to be believed, “members of the Lebanese government received calls from U.S. and French diplomats who were unnerved by Nasrallah’s speech, in which he warned that Hezbollah was prepared to respond to any Israeli attack…at any time and in any place.” Unfortunately, the focus being given to that particular aspect of Nasrallah’s speech enables all involved to either ignore or at least minimize the background and context of his rhetoric. It also allows them to balance the speech’s appeasement with the threats it conveys. Of particular relevance is the beginning of Nasrallah’s monologue, in which he mentioned that the joint patrol attacked was not in Quneitira to take any action against Israel, or his conclusion, in which he insisted, “we don’t want war with Israel but do not fear it.”

The January 18 attack became important not only because of where it occurred (Quneitira, Syria), but also because an Iranian general was killed in the process. By extension, Sayyed Nasrallah’s warning about “changing the rules of engagement” became important because of the vociferous Iranian statements that followed—the bulk of which were anything but subtle. In a brief review of the events that occurred subsequent to the attack, the increasingly famous Qassem Suleimani visited Beirut several days before Nasrallah’s speech to pay tribute to (the late) elder and younger Mughniyehs. Stated otherwise, Suleimani was likely in Beirut to supervise the retaliation operation. Similarly, Alaeddin Boroujerdi, chairman of the Iranian parliament’s national security and foreign policy committee, attended the rally held while Nasrallah gave his speech! Although these gestures may add credibility to Nasrallah’s threats, they also imply that making good on them will not be left to Hezbollah, but to its patrons. Moreover, although the implication may provide some relief to those who do not want to see other rogue, non-state groups contribute to the region’s prevailing instability, it is indeed more bad news for other Lebanese political actors. After all, the wheels set in motion by the January 18 attack simply reinforced the fact that they matter very little to Hezbollah generally or individually.

However challenging it may be to admit, Hezbollah’s agenda as a subset of Iran’s grand regional strategy is easier to read than its domestic counterpart. In reality, Hezbollah’s agenda for Lebanon is focused completely on maintaining the image that “its” Shia community is cohesive and free of dissent and ensuring that the mainstream portion of that community remains convinced that everything Hezbollah does or fails to do is in the best interests of that community. Yet things become much more complex when we add that keeping the Lebanese Shia convinced of Hezbollah’s omniscient rectitude is the essential ingredient that enables it to help achieve Iran’s overarching regional agenda. It is clear to anyone who observes post hoc ergo propter hoc the entire Lebanese Shia scene(rather than its Hezbollah distillate), that the IDF attack which killed Jihad Imad Mughniyeh (among others) placed significant pressure on Hezbollah vis-à-vis its biaa hadina.

Compared to the broader Joumhour, Hezbollah has drawn the bulk of the manpower it needs to sustain its adventures in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and elsewhere from the biaa hadina—the same “community” that continues to receive Lebanese corpses from those destinations. Aside from the “blood debts” that biaa is already struggling to pay, it is now being asked to make good on others, such as the outstanding bill represented by the Sunni Gulf states. During the al-Mayadeen interview, for instance, Nasrallah harshly criticized the Bahraini regime and likened its rulers to “Zionists.” Not only did those remarks prompt the Arab League to condemn Hezbollah’s “repetitive interference in the internal affairs of Bahrain,” but it also led Bahrain to consider expelling a certain number of Lebanese Shia. In sum, aside from the bloody price being demanded of the Lebanese Shia to underwrite Hezbollah’s adventures, the community—the biaa—is also expected to afford less brutal yet nonetheless painful costs.

Hezbollah has yet to avenge the February 12, 2008 attack in Syria that killed Imad Mughniyeh. Ignoring the death of his son, without so much as a vague promise of retribution “at the right moment and place,” would have been unbearable for a biaa which now feels that it is being attacked from all sides. Of course, this does not infer that the biaa is seeking all-out war on a scale similar to (or greater than) that of the July 2006 War. Ultimately, it considers Hezbollah a military apparatus and guarantor of its interests, and the biaa is seeking proof that Hezbollah, the community’s “guardian angel,” can still live up to the image it created for itself. In other words, the January 18 attack near Quneitira compelled Hezbollah to address (among other things) the crisis of confidence its biaa is experiencing.

We cannot subscribe fully to anything that has been discussed and/or published recently about Hezbollah’s internal difficulties. We understand, however, that these include security breaches (which may help explain Israel’s success in the Quneitira attack), financial problems (characterized by some as approaching “bankruptcy”), questions about its Syrian adventure (which is costing the biaa an ever-increasing share of its youth) and the prevailing opinion among Lebanese (including Shia) that the country is heading in the “wrong direction.” But no matter how we choose to minimize these issues, they impose an undeniable sense of reality. Regardless of Hezbollah’s travails, it was left to Nasrallah to address this crisis of confidence. Further, believing that the repercussions of the January 18 attack were strictly political-military and supra-national in nature is tantamount to ideological color blindness, a “condition” that can be treated by replacing intellectual laziness with timely facts about Lebanon’s Shia community, especially those who reside in south Lebanon.

It is unnecessary to cite a litany of references and footnotes which confirm that since implementation of UNSC resolution 1701 following the July 2006 War, south Lebanon has been experiencing degrees of peace (despite some scattered incidents) and prosperity that would shock Lebanese living elsewhere in the country. While Hezbollah’s involvement in Syria has placed the Bekaa and Dahiyeh on the frontlines of the confrontation, today, the only portion of the country that has escaped the spreading conflict is south Lebanon. Thus, it appears south Lebanon is the sole remaining safe haven for Lebanese Shia. Based on the foregoing, it would be shortsighted to ignore the fatigue being experienced by Lebanon’s Shia community while assessing Hezbollah’s homeopathic response to the Quneitira attack. After all, that community would become the first victims of Hezbollah’s “teaser” response in the disputed Shebaa farms region—which certainly has the potential to be the catalyst for a broader conflict.

Several days after the Quneitira/Shebaa episode, Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman prophesied somewhat biblically that, “A fourth operation in the Gaza Strip is inevitable, just as a third Lebanon war is inevitable.” While Lieberman’s forecast may ultimately prove correct (regardless of the magnitude involved or which “camp” makes the first move), we can be sure that Hezbollah will not make the decision to “light the match” unilaterally. Hezbollah’s role in the Syrian conflict has certainly proved the organization’s instrumental role in Iran’s plans for regional expansion, but it also demonstrated quite clearly that Hezbollah’s moves are subject to the desires of the Iranian regime.

In the meantime, of course, Hezbollah cannot neglect its domestic homework: it must maintain the “divine” image it inculcated within mainstream Lebanese Shia, and it is already doing just that. The proof can be made by the Poll and by the Rocket—yet neither form seems irrefutable. On February 1, following Nasrallah’s speech and Hezbollah’s retaliatory attack in the contested Shebaa farms region, a bus filled with Lebanese Shia visiting Shia shrines in Damascus exploded. Half a dozen people were killed and triple that number were injured. Understandably, the attack was not especially unique compared to the numerous terrorist attacks that take place every day, so it did not enjoy wide media coverage and was “filed” routinely in the category of Syria-related daily security incidents. Nevertheless, the lack of media attention certainly does not diminish the impact of that attack on the Lebanese Shia community, which was still struggling to recover from the Quneitira episode. Popular sentiment regarding this spate of events usually invokes a well-known colloquial proverb: “good news which proves to be wrong is worse than bad news….”

Near the end of a two and a half hour interview with Hezbollah’s secretary general broadcast January 15 by al-Mayadeen television, host Ghassan ben Jeddo asked, “Speaking frankly, do you believe the social and sectarian milieu still supports you [Hezbollah] and represents a viable core?” Sayyed Nasrallah responds affirmatively. As proof, he refers to some public opinion surveys conducted by “research centers” managed by “Shia Americans,” and he made sure to note that those involved were “Shia connected to the American Embassy.”

Of course, his mention of “research centers” was a direct reference to Hayya Bina, and the survey he acknowledged was the February 2014 Hayya Bina poll, the results of which were published the following August in Arabic and English.

Apparent in Nasrallah’s comments is the common, paranoid obsession that sees the hand of the “American Embassy” behind all such research efforts. Similarly, his indiscriminate reference to the Hayya Bina poll is yet another reiteration of the joint Nasrallah/Hezbollah argument that seeks to assert the organization’s righteousness by emphasizing the credibility of literature produced by their political opponents (or enemies)...as long as those “sources” support their allegations. Beyond these anecdotal facts, Nasrallah’s mere reference to the Hayya Bina poll instantly enhanced its reliability and publicity—even though the responses collected via that poll are not always favorable to his organization. Thus, we owe Sayyed Nasrallah a debt of gratitude for having acknowledged the very best way to measure Hezbollah’s popularity within the Shia community.

Hezbollah often refers to its constituency as al-biaa al-hadina or Joumhour al-Moqawama (“the lapping environment” and “the public of the Resistance,” respectively). While these terms are often used interchangeably, their connotation is anything but similar.

In a nutshell, Joumhour al-Moqawama is far less restrictive than al-biaa al-hadina, as the former encompasses everyone who supports “the Resistance” regardless of sectarian affiliation or nationality. Conversely, the inclusiveness of Joumhour al-Moqawama, which has no preconditions for membership, differs substantially from al-biaa al-hadina, which refers more exclusively to the larger Shia community with its semantic complement of intimacy and worldliness.

Much to his credit, al-Mayadeen host Ghassan ben Jeddo chose not to whitewash his pivotal question. Instead, he remained on point by asking about the “the lapping environment,” i.e., the Shia community. But while the true nature of the question seems clear, it requires additional illumination.

In Lebanon, discussions about political representation of the Lebanese Shia community typically utilize “local” parlance to identify the “Shia duo,” comprised of Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, as the pillars of that representation. And while both organizations have their respective MPs, ministers and other shares of the Lebanese pie, when the discussion centers on “the lapping environment,” we seem to overlook that inherent division and focus instead on something beyond. In reality, however, Hezbollah’s popularity is not a partisan issue! After all, whether we like it or not, that vague reference to Hezbollah also encompasses its organizational affiliates and clientele-oriented architecture, both of which enjoy bits and pieces of Hezbollah’s share of the Lebanese pie. Thus, when we describe Hezbollah’s “lapping environment,” the larger Lebanese Shia community is automatically inferred. Clearly, the same cannot be said for the Amal Movement. Moreover, the question bin Jeddo asked of Nasrallah simply could not be answered by Nabih Berri (the Amal head). Despite the fact that Berri sees himself as heir to Sayyed Moussa Sadr (to whom the Lebanese Shia community owes its ascendancy on Lebanon’s political horizon), Sadr’s populist legacy and eventual “Movement of the Deprived” (the forerunner of the Amal Movement) seem to have shifted toward Hezbollah. A nostalgic, former senior Amal personality describes that transformation in militaristic terms: “Amal’s constituency is ‘occupied’ to a large extent by Hezbollah.” Unfortunately, although this metaphor is tempting because it suggests that simply undoing that “occupation” would force a return to the status quo ante, it fails to account for today’s sectarian related identity polarization (in Lebanon and throughout the region). Under this still emerging model, within-group partisan competition is no longer based on programmatic rivalry but on whom can best represent, protect and advocate the interests of a given sect in the face of other sects. Clearly, the matter of perception changes the situation little if at all.

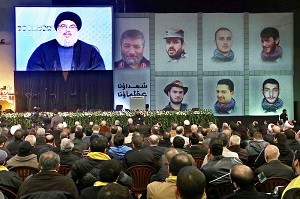

In view of the foregoing, the logical conclusion is that no one in Lebanon—at least in the near term—can emerge as a viable competitor to Hezbollah. Consequently, questioning Hezbollah’s popularity among Lebanese Shia revolves less around the organization gaining or losing popularity vis-à-vis other competitors than it does to political cohesion within the community—or at least the image of unity and self-confidence to which the mainstream portion of that community subscribes. Further, an appreciation of this conceptual framework is necessary before one can genuinely understand the developments that began to unfold on January 18, 2015. That Sunday, Israel Defense Forces (IDF) helicopters attacked a joint Hezbollah-Iranian Revolutionary Guard convoy in Quneitira killing those in the two vehicles targeted, including an Iranian general and the son of Imam Mughniyyeh. Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah finally appeared January 30—on a mega screen—to comment on Hezbollah’s retaliatory attack conducted two days before in the contested Shebaa farms region.

Much has already been, and will continue to be said about Nasrallah’s speech, particularly his announcement that “the Quneitira attack also destroyed the rules of engagement that had previously governed military confrontations between Hezbollah and Israel in south Lebanon.” Assuming an-Nahar is to be believed, “members of the Lebanese government received calls from U.S. and French diplomats who were unnerved by Nasrallah’s speech, in which he warned that Hezbollah was prepared to respond to any Israeli attack…at any time and in any place.” Unfortunately, the focus being given to that particular aspect of Nasrallah’s speech enables all involved to either ignore or at least minimize the background and context of his rhetoric. It also allows them to balance the speech’s appeasement with the threats it conveys. Of particular relevance is the beginning of Nasrallah’s monologue, in which he mentioned that the joint patrol attacked was not in Quneitira to take any action against Israel, or his conclusion, in which he insisted, “we don’t want war with Israel but do not fear it.”

The January 18 attack became important not only because of where it occurred (Quneitira, Syria), but also because an Iranian general was killed in the process. By extension, Sayyed Nasrallah’s warning about “changing the rules of engagement” became important because of the vociferous Iranian statements that followed—the bulk of which were anything but subtle. In a brief review of the events that occurred subsequent to the attack, the increasingly famous Qassem Suleimani visited Beirut several days before Nasrallah’s speech to pay tribute to (the late) elder and younger Mughniyehs. Stated otherwise, Suleimani was likely in Beirut to supervise the retaliation operation. Similarly, Alaeddin Boroujerdi, chairman of the Iranian parliament’s national security and foreign policy committee, attended the rally held while Nasrallah gave his speech! Although these gestures may add credibility to Nasrallah’s threats, they also imply that making good on them will not be left to Hezbollah, but to its patrons. Moreover, although the implication may provide some relief to those who do not want to see other rogue, non-state groups contribute to the region’s prevailing instability, it is indeed more bad news for other Lebanese political actors. After all, the wheels set in motion by the January 18 attack simply reinforced the fact that they matter very little to Hezbollah generally or individually.

Compared to the broader Joumhour, Hezbollah has drawn the bulk of the manpower it needs to sustain its adventures in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and elsewhere from the biaa hadina—the same “community” that continues to receive Lebanese corpses from those destinations. Aside from the “blood debts” that biaa is already struggling to pay, it is now being asked to make good on others, such as the outstanding bill represented by the Sunni Gulf states. During the al-Mayadeen interview, for instance, Nasrallah harshly criticized the Bahraini regime and likened its rulers to “Zionists.” Not only did those remarks prompt the Arab League to condemn Hezbollah’s “repetitive interference in the internal affairs of Bahrain,” but it also led Bahrain to consider expelling a certain number of Lebanese Shia. In sum, aside from the bloody price being demanded of the Lebanese Shia to underwrite Hezbollah’s adventures, the community—the biaa—is also expected to afford less brutal yet nonetheless painful costs.

Hezbollah has yet to avenge the February 12, 2008 attack in Syria that killed Imad Mughniyeh. Ignoring the death of his son, without so much as a vague promise of retribution “at the right moment and place,” would have been unbearable for a biaa which now feels that it is being attacked from all sides. Of course, this does not infer that the biaa is seeking all-out war on a scale similar to (or greater than) that of the July 2006 War. Ultimately, it considers Hezbollah a military apparatus and guarantor of its interests, and the biaa is seeking proof that Hezbollah, the community’s “guardian angel,” can still live up to the image it created for itself. In other words, the January 18 attack near Quneitira compelled Hezbollah to address (among other things) the crisis of confidence its biaa is experiencing.

We cannot subscribe fully to anything that has been discussed and/or published recently about Hezbollah’s internal difficulties. We understand, however, that these include security breaches (which may help explain Israel’s success in the Quneitira attack), financial problems (characterized by some as approaching “bankruptcy”), questions about its Syrian adventure (which is costing the biaa an ever-increasing share of its youth) and the prevailing opinion among Lebanese (including Shia) that the country is heading in the “wrong direction.” But no matter how we choose to minimize these issues, they impose an undeniable sense of reality. Regardless of Hezbollah’s travails, it was left to Nasrallah to address this crisis of confidence. Further, believing that the repercussions of the January 18 attack were strictly political-military and supra-national in nature is tantamount to ideological color blindness, a “condition” that can be treated by replacing intellectual laziness with timely facts about Lebanon’s Shia community, especially those who reside in south Lebanon.

It is unnecessary to cite a litany of references and footnotes which confirm that since implementation of UNSC resolution 1701 following the July 2006 War, south Lebanon has been experiencing degrees of peace (despite some scattered incidents) and prosperity that would shock Lebanese living elsewhere in the country. While Hezbollah’s involvement in Syria has placed the Bekaa and Dahiyeh on the frontlines of the confrontation, today, the only portion of the country that has escaped the spreading conflict is south Lebanon. Thus, it appears south Lebanon is the sole remaining safe haven for Lebanese Shia. Based on the foregoing, it would be shortsighted to ignore the fatigue being experienced by Lebanon’s Shia community while assessing Hezbollah’s homeopathic response to the Quneitira attack. After all, that community would become the first victims of Hezbollah’s “teaser” response in the disputed Shebaa farms region—which certainly has the potential to be the catalyst for a broader conflict.

In the meantime, of course, Hezbollah cannot neglect its domestic homework: it must maintain the “divine” image it inculcated within mainstream Lebanese Shia, and it is already doing just that. The proof can be made by the Poll and by the Rocket—yet neither form seems irrefutable. On February 1, following Nasrallah’s speech and Hezbollah’s retaliatory attack in the contested Shebaa farms region, a bus filled with Lebanese Shia visiting Shia shrines in Damascus exploded. Half a dozen people were killed and triple that number were injured. Understandably, the attack was not especially unique compared to the numerous terrorist attacks that take place every day, so it did not enjoy wide media coverage and was “filed” routinely in the category of Syria-related daily security incidents. Nevertheless, the lack of media attention certainly does not diminish the impact of that attack on the Lebanese Shia community, which was still struggling to recover from the Quneitira episode. Popular sentiment regarding this spate of events usually invokes a well-known colloquial proverb: “good news which proves to be wrong is worse than bad news….”

Print

Print Share

Share